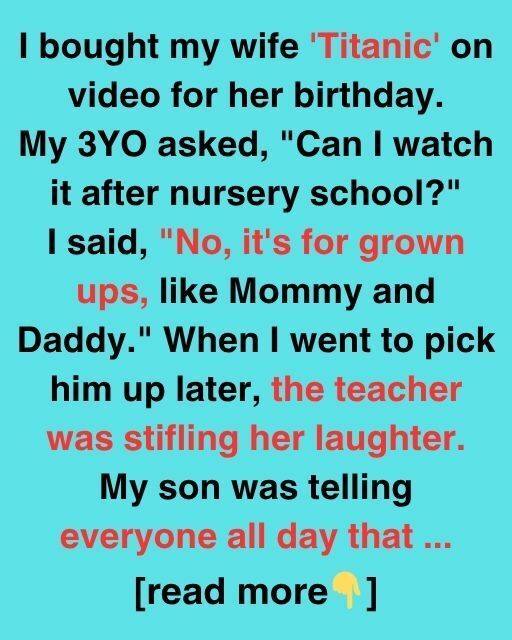

On my wife’s birthday, I handed her a wrapped DVD—Titanic—because romance, nostalgia, and a little Leo/Kate never hurt anyone. As she peeled back the paper, our three-year-old, Max, tipped his head and asked, perfectly serious, “Can I watch it after nursery?”

Without thinking, I said, “Not this one, buddy. That’s for grown-ups—just Mommy and Daddy.”

At pickup that afternoon, his teacher was trying very hard not to laugh. Apparently, from morning circle to dismissal, our sweet child informed teachers, classmates, and a handful of startled parents that “Mommy and Daddy watch Titanic alone at night because it’s for grown-ups only.” I did damage control at the classroom door.

“Just to clarify,” the teacher asked, eyes dancing, “this Titanic… the ship?”

I nodded, face warm. “With Leonardo DiCaprio.”

She finally let the chuckle go. “Ah. We weren’t sure if it was… some other kind of Titanic.”

When I told my wife, she laughed so hard she nearly fell off the couch. It became our go-to icebreaker—instant laughs, minimal effort.

Somewhere under the humor, something else started growing. Max became obsessed—not with the movie, but with the ship. The real story. The bigness and the breaking. He asked questions like a tiny historian.

“What made it sink? Did anyone survive? Was there a slide? Was it like a pirate ship?”

Duplo towers turned into ocean liners, complete with uneven smokestacks and a shampoo-bottle iceberg. Bathtime became a rescue operation with conditioner-caps as lifeboats. It was charming, and it didn’t fade.

One evening over chicken nuggets, he asked, “Daddy, why didn’t the captain see the iceberg?”

I tried to translate something complicated into preschool. “Sometimes people think they’re in control when they’re not,” I said. “They go too fast and don’t notice what’s ahead.”

He nodded, like he was shelving the thought. Then he whispered, “I think that’s what happened to you and Mommy.”

I blinked. “What do you mean, buddy?”

He looked at me with a strange, soft certainty. “When I was in Mommy’s tummy, you and her were going really fast. And you didn’t see your iceberg.”

It hit like cold water. Max had been a surprise. We’d been together a year when the test turned positive. We married quickly, bought a small house, took steady jobs, and did our best to keep everything afloat. We weren’t unhappy, exactly. Just busy. Parallel. Co-captains on decks that rarely crossed.

That night, after Max fell asleep, I told my wife what he’d said. The smile in her eyes faded.

“Oh.”

We finally had the conversation we’d been skirting for months—the kind you keep pushing to later while your life hums its way around it. No yelling. No scorekeeping. Just naming what we’d both felt: not unhappy, but separate. Running fast. Missing what was right in front of us.

We made small changes. I left work early on Fridays and banned email after dinner. She started painting again—quiet afternoons where the house smelled like acrylic and coffee. We put the phones away more. We said yes to walks and no to things we didn’t mean. Little course-corrections.

Meanwhile, Max kept being Max. The DVD gathered dust. He bounced from ships to dinosaurs to volcanoes to black holes. His questions never lost their edge.

At five: “Why do you smile when you’re tired?”

At six: “Mommy, you should write a book about your dreams.”

At seven: “I think Grandpa visits me in my sleep. We talk without words.”

We called it imagination and left the hallway light on.

When he turned nine, we ended up in Halifax—my wife for work, Max still buzzing from a geography unit on Canada. We wandered into the Maritime Museum and stumbled straight into the Titanic exhibit.

Max went quiet. He stood before a recovered deck chair as if it were a person. He traced the big wall map of the ship’s last hours and said, almost to himself, “Here. This is where it happened.”

“Did you learn that at school?” my wife asked.

He shook his head. “I just know.”

Back at the hotel, he asked if he could finally watch Titanic. He was ready. We said yes.

He barely moved, eyes wide, fists tight. When it ended, he said softly, “They were too proud. That’s why it sank.”

The next morning, I found a note in hotel stationery, in his careful hand: Even the largest ships need to be humble. Or else they will sink.

I tucked it into my wallet.

He grew into himself. He preferred books to video games, conversation to noise. He made friends with our elderly neighbors. I once found him in the yard with Mr. Holland—the reclusive man two doors down—both of them laughing. Later, I asked what they’d talked about.

“He misses Mrs. Holland,” Max said. “He thinks no one remembers her. I told him to tell me everything. I said I’d remember.”

That winter, Mr. Holland died. At the funeral, they asked if anyone wanted to speak. Max raised his hand. Hands shaking, he stood at the front and said, “I didn’t know Mr. Holland for very long. But I could tell he loved Mrs. Holland because his smile changed when he talked about her. I think she knew.”

No one had a dry eye. Including me.

By thirteen, my wife and I had changed too. We shifted careers. We started volunteering. We shrank our lives in the best ways—smaller circles, deeper roots. We learned to spot our icebergs, not just plow into them.

Max joined a mentorship program—not because he needed help, but because he wanted to give it. One evening, I picked him up, and he was quiet in the car, looking older in the way kids do when they’ve been paying attention.

“How’d it go?”

“Good.” A pause. “One kid’s dad left. I told him mine stayed.” He looked at me. “Sometimes staying is harder than leaving. Thanks for staying, Dad.”

I had to pull over. Tears do what they want.

High school came and went. College, too. Max studied psychology. “People are like ships,” he said once. “Some drift. Some sink. Some anchor too deep. But all carry stories.”

On the day he graduated, he handed us a gift. A DVD case.

We opened it: Titanic. The same copy we’d bought all those years ago. Inside, a note:

Thank you for steering me through life—even when we couldn’t see the icebergs. —Max, your first crewmate.

We cried. We hugged. We laughed like we used to. That night, we finally watched Titanic again. Just us. No rushing. We watched every minute of the film—and, somehow, every minute of the last decade threaded through it. The near-misses. The course changes. The quiet saves.

When the credits rolled, my wife leaned into me. “Funny,” she said. “The thing that once made us laugh now feels like what brought everything full circle.”

Because sometimes the iceberg isn’t the end. Sometimes it’s the moment you start steering with your heart.

If there’s a lesson, it’s this: don’t outrun your weather. Don’t ignore the warnings because the deck looks pretty and the band’s still playing. Be humble, even when you feel unsinkable. And never underestimate the quiet wisdom of the small people watching you from their booster seats—they see more than we think.

If this story moved you, share it. Someone out there is speeding toward an iceberg. Maybe this is the nudge that helps them slow down.

Even the largest ships need to be humble. Or else… they will sink.